Tsunamis are comprised of a series of waves which often look like walls of water. The first wave may not be the largest, and often it is the 2nd, 3rd, 4th or even later waves that are the biggest. After one wave inundates, or floods inland, it recedes seaward often as far as a person can see so the seafloor is exposed making marine life not normally seen very visible. The next wave then rushes ashore within minutes and carries with it significant volumes of floating debris destroyed by previous waves. When waves enter harbors, very strong and dangerous water currents are generated that can easily break ship moorings, and bores that travel far inland can be formed when tsunamis enter rivers or other waterway channels.

From the source, tsunami waves travel outward in all directions. They can attack the shoreline and be dangerous for hours, with waves coming from minutes to hours apart from each other.

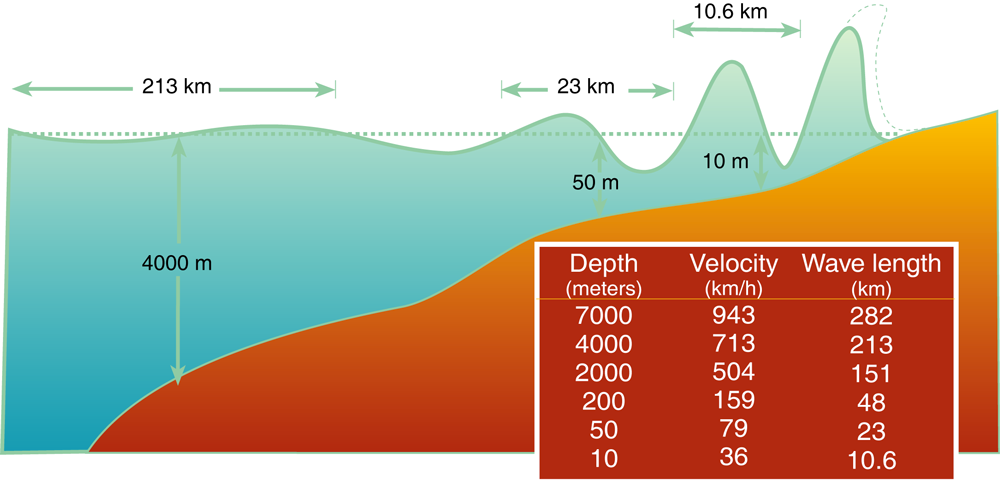

Tsunamis travel up to jet airliner speeds (from 80 – 1,000 kilometres per hour) in the deep ocean where the waves are only centimeters high (often a few tens of centimetres) and cannot be felt aboard ship. When tsunamis hit shallow water, their speed reduces and the height grows tremendously. The topography of the coastline as well as the ocean floor will influence the size of the wave. That is why a small tsunami at one beach can be a giant wave a few miles away.

Tsunamis generally crest up to 10-m high heights but can impact land with waves as high as 100 feet or more, striking with a devastating force, and quickly flood all low-lying coastal areas.

A tsunami that travels over long regions of water has the potential for greater wave heights and speed than a local tsunami.

As a tsunami wave enters shallow water, the wave speed slows and the height increases, creating destructive, life-threatening waves.

[source]In the ocean, normally waves are generated by wind and can be described through their amplitude, which is the height of the wave, and wavelength, which is the distance from one wave crest to the other. The wavelength is a factor that distinguishes tsunamis from wind waves: a tsunami wavelength is considerably longer than a wind wave wavelength; it can be more than 200 km long. The wavelength is closely linked to the sea depth. As the sea depth decreases, the wavelength decreases. At the same time, the height of the wave increases. Near the shoreline the wave can assume the shape of a wall, up to tens of metres high, with a massive destructive power. The speed of a tsunami wave can be simply expressed by the formula v= where g is the acceleration of gravity (9,8 m/s2), and h is the depth of the sea expressed in metres.

Tsunamis cause major damage to towns and even deaths when it has reached on land. All tsunamis are potentially dangerous, even though they may not damage every coastline they strike.